In the trenches rats were a big problem. They ate up both the corpses and the rations of soldiers.

In the trenches rats were a big problem. They ate up both the corpses and the rations of soldiers.  German soldier moves through poison gas

German soldier moves through poison gasGAS ATTACK 1916 (Eyewitnesstohistory)

Arthur Empey was an American living in New Jersey when war consumed Europe in 1914. Enraged by the sinking of the Lusitania and loss of the lives of American passengers, he expected to join an American army to combat the Germans. When America did not immediately declare war, Empey boarded a ship to England, enlisted in the British Army (a violation of our neutrality law, but no one seemd to mind) and was soon manning a trench on the front lines.

Emprey survived his experience and published his recollections in 1917. We join his story after he has been made a member of a machine gun crew and sits in a British trench peering towards German lines. Conditions are perfect for an enemy gas attack - a slight breeze blowing from the enemy's direction - and the warning has been passed along to be on the lookout:

"We had a new man at the periscope, on this afternoon in question; I was sitting on the fire step, cleaning my rifle, when he called out to me: 'There's a sort of greenish, yellow cloud rolling along the ground out in front, it's coming ---'

But I waited for no more, grabbing my bayonet, which was detached from the rifle, I gave the alarm by banging an empty shell case, which was hanging near the periscope. At the same instant, gongs started ringing down the trench, the signal for Tommy to don his respirator, or smoke helmet, as we call it.

Gas travels quietly, so you must not lose any time; you generally have about eighteen or twenty seconds in which to adjust your gas helmet.

A gas helmet is made of cloth, treated with chemicals. There are two windows, or glass eyes, in it, through which you can see. Inside there is a rubber-covered tube, which goes in the mouth. You breathe through your nose; the gas, passing through the cloth helmet, is neutralized by the action of the chemicals. The foul air is exhaled through the tube in the mouth, this tube being so constructed that it prevents the inhaling of the outside air or gas. One helmet is good for five hours of the strongest gas. Each Tommy carries two of them slung around his shoulder in a waterproof canvas bag. He must wear this bag at all times, even while sleeping. To change a defective helmet, you take out the new one, hold your breath, pull the old one off, placing the new one over your head, tucking in the loose ends under the collar of your tunic.

For a minute, pandemonium reigned in our trench, - Tommies adjusting their helmets, bombers running here and there, and men turning out of the dugouts with fixed bayonets, to man the fire step.

Reinforcements were pouring out of the communication trenches.

Our gun's crew was busy mounting the machine gun on the parapet and bringing up extra ammunition from the dugout.

German gas is heavier than air and soon fills the trenches and dugouts, where it has been known to lurk for two or three days, until the air is purified by means of large chemical sprayers. We had to work quickly, as Fritz generally follows the gas with an infantry attack. A company man on our right was too slow in getting on his helmet; he sank to the ground, clutching at his throat, and after a few spasmodic twistings, went West (died). It was horrible to see him die, but we were powerless to help him. In the corner of a traverse, a little, muddy cur dog, one of the company's pets, was lying dead, with his two paws over his nose.

It's the animals that suffer the most, the horses, mules, cattle, dogs, cats, and rats, they having no helmets to save them. Tommy does not sympathize with rats in a gas attack.

At times, gas has been known to travel, with dire results, fifteen miles behind the lines.

A gas, or smoke helmet, as it is called, at the best is a vile-smelling thing, and it is not long before one gets a violent headache from wearing it.

Our eighteen-pounders were bursting in No Man's Land, in an effort, by the artillery, to disperse the gas clouds.

The fire step was lined with crouching men, bayonets fixed, and bombs near at hand to repel the expected attack.

Our artillery had put a barrage of curtain fire on the German lines, to try and break up their attack and keep back reinforcements.

I trained my machine gun on their trench and its bullets were raking the parapet. Then over they came, bayonets glistening. In their respirators, which have a large snout in front, they looked like some horrible nightmare.

All along our trench, rifles and machine guns spoke, our shrapnel was bursting over their heads. They went down in heaps, but new ones took the place of the fallen. Nothing could stop that mad rush. The Germans reached our barbed wire, which had previously been demolished by their shells, then it was bomb against bomb, and the devil for all.

Suddenly, my head seemed to burst from a loud 'crack' in my ear. Then my head began to swim, throat got dry, and a heavy pressure on the lungs warned me that my helmet was leaking. Turning my gun over to No. 2, I changed helmets.

The trench started to wind like a snake, and sandbags appeared to be floating in the air. The noise was horrible; I sank onto the fire step, needles seemed to be pricking my flesh, then blackness.

I was awakened by one of my mates removing my smoke helmet. How delicious that cool, fresh air felt in my lungs.

A strong wind had arisen and dispersed the gas.

They told me that I had been 'out' for three hours; they thought I was dead.

The attack had been repulsed after a hard fight. Twice the Germans had gained a foothold in our trench, but had been driven out by counter- attacks. The trench was filled with their dead and ours. Through a periscope, I counted eighteen dead Germans in our wire; they were a ghastly sight in their horrible-looking respirators.

I examined my first smoke helmet, a bullet had gone through it on the left side, just grazing my ear, the gas had penetrated through the hole made in the cloth.

Out of our crew of six, we lost two killed and two wounded.

That night we buried all of the dead, excepting those in No Man's Land. In death there is not much distinction, friend and foe are treated alike.

After the wind had dispersed the gas, the R. A. M. C. got busy with their chemical sprayers, spraying out the dugouts and low parts of the trenches to dissipate any fumes of the German gas which may have been lurking in same."

References:

Empey, Arthur Guy, Over The Top (1917); Lloyd, Alan, The War In The Trenches (1976)

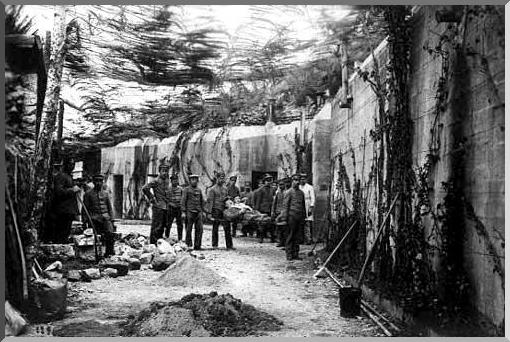

German bunkers. The Allies hated them. Shells made no impact on them. The man in the white coat is a doctor.

German bunkers. The Allies hated them. Shells made no impact on them. The man in the white coat is a doctor. Wearing gas masks, German soldiers wade through a gas attack by the British.

Wearing gas masks, German soldiers wade through a gas attack by the British. Germans walk past an abandoned British tank at Verdun.

Germans walk past an abandoned British tank at Verdun. By 1917 the tide had changed. Incessant bombardment by the Allies shook up the German defences in the trenches.

By 1917 the tide had changed. Incessant bombardment by the Allies shook up the German defences in the trenches.QUOTES

I believe that the war is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I believe that this war, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of agression and conquest.British Captain S. Sassoon, in "The Times", 30 July 1917

The German machine-gun made a big impact on the war.

The German machine-gun made a big impact on the war. German soldiers move forward with their machine gun

German soldiers move forward with their machine gun A German soldier dies in as an Allied shell hits the German gun position. Another German soldier had died before.

A German soldier dies in as an Allied shell hits the German gun position. Another German soldier had died before.

TRENCH WARFARE QUOTES

You were between the devil and the deep blue sea. If you go forward, you`ll likely be shot, if you go back you`ll be court-martialled and shot, so what the hell do you do? What can you do? You just go forward because that`s the only bloke you can take your knife in, that`s the bloke you are facing.-- A British soldier

Germans huddle around their dead colleague.

Germans huddle around their dead colleague.WW1 QUOTES

For a young man who had a long and worthwile future awaiting him, it was not easy to expect death almost daily. However, after a while I got used to the idea of dying young. Strangely, it had a sort of soothing effect and prevented me from worrying too much. Because of this I gradually lost the terrible fear of being wounded or killed.-- Reinhold Spengler, A German soldier

A German soldiers dresses a wounded British soldier

A German soldiers dresses a wounded British soldier

QUOTES

-- Hans Otto Schette, German soldierThe whole earth is ploughed by the exploding shells and the holes are filled with water, and if you do not get killed by the shells you may drown in the craters. Broken wagons and dead horses are moved to the sides of the road, also many dead soldiers lie here. Wounded soldiers who died in the ambulance have been unloaded and their eyes stare at you. Sometimes an arm or leg is missing. Everybody is rushing, running, trying to escape almost certain death in this hail of enemy shells. Today I have seen the real face of war.

These Germans are quite cheerful as they head for the front. Their aim was, as their superiors wanted it, to 'bleed the French to death'. Deployed in this war of attrition only a few of these soldiers returned alive. Summer 1915.

These Germans are quite cheerful as they head for the front. Their aim was, as their superiors wanted it, to 'bleed the French to death'. Deployed in this war of attrition only a few of these soldiers returned alive. Summer 1915.

QUOTES

The enemy started to advance in mass down the railway cutting, about 800 yards off, and Maurice Dease fired his two machine-guns into them and absolutely mowed them down. I should judge without exaggeration that he killed at least 500 in two minutes. The whole cutting was full of bodies and this cheered us all up.

Lieutenant K. Tower, Royal Fusiliers, 1914

Lieutenant K. Tower, Royal Fusiliers, 1914

A surly German guards British POWS

A surly German guards British POWSQUOTES

A soldier (who had just returned from the Western Front) was so disordered while he was going down the stairs into the London tube station, he became suddenly aware of the crowds of people coming up, he looked haggardly about, and evidently mistaking the hollow space below for the trenches and the ascending crowd for Germans, fixed his bayonet and charged. But for the women constable on duty at the turn of the staircase, who was quick enough to divine his trouble and hang on to him with all her strength to prevent his forward advance, he would have wounded many and caused danger and panic.

British policewoman Mary Allen, in her autobiography

British policewoman Mary Allen, in her autobiography

This guy has just made two Belgian girlfriends.

This guy has just made two Belgian girlfriends. The German trenches were usually very well built. There were strong and they had loop-holes. The picture shows two soldiers throwing hand-grenades while two others take an aim at the enemy.

The German trenches were usually very well built. There were strong and they had loop-holes. The picture shows two soldiers throwing hand-grenades while two others take an aim at the enemy.RELATED ARTICLES

-- Rare German WW1 pictures: Part 1

-- Rare German WW1 pictures: Part 3